'Torture Memos' vs. Academic Freedom

A review of a Berkeley law professor's memos to the White House about counterterrorism policies prompts calls for his job

Printer friendly | article | Subscribe | Order reprints |

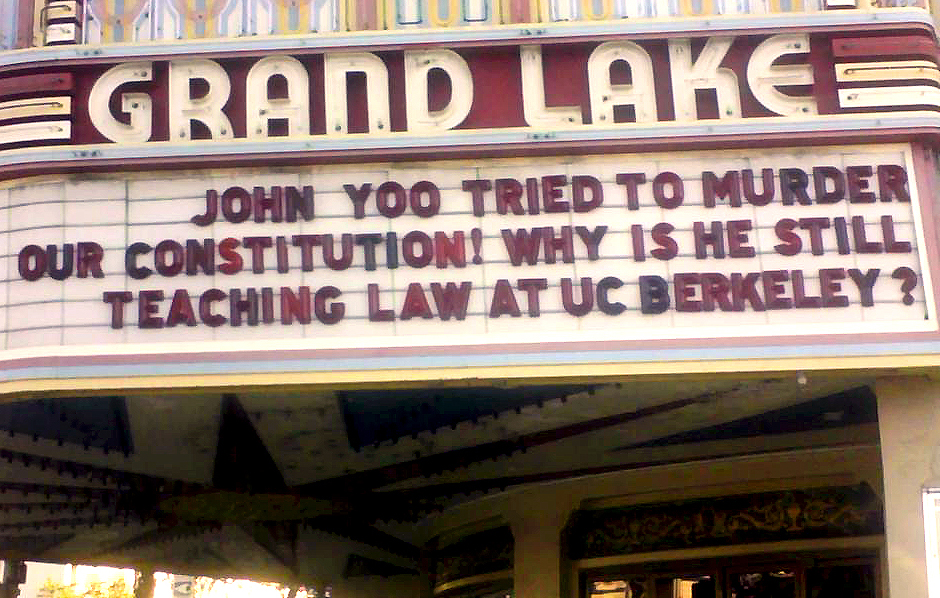

When people gathered last May for the commencement ceremony at the University of California at Berkeley's Boalt Hall School of Law, they were greeted by chanting activists from the National Lawyers Guild and other left-wing groups.

The university, protesters shouted, should fire John C. Yoo, a tenured professor who has taught at the law school since 1993. While on leave at the U.S. Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel between 2001 and 2003, Mr. Yoo drafted what have come to be known as the "torture memos"Â -- a series of secret memoranda that gave benediction to President George W. Bush's interrogation and surveillance policies.

Some scholars believe that Mr. Yoo's memoranda were so shoddy that they amounted to professional misconduct. Several of those critics also think that Mr. Yoo's academic job should be in jeopardy. But others -- including some who agree that Mr. Yoo's memoranda were pernicious -- argue that penalizing Mr. Yoo for his work in Washington could set a troubling precedent for academic freedom.

Now the debate over Mr. Yoo's presence at Berkeley has taken on new urgency. At the beginning of March, the government released several previously undisclosed memoranda by Mr. Yoo. And the Justice Department will soon complete a review of his conduct. According to a Newsweek report, the department might allege that Mr. Yoo improperly colluded with the White House to craft justifications for dubious counterterrorist policies. It could be the credible charge of misconduct that critics have been waiting for.

A Higher Standard

At the center of the storm sits Christopher Edley Jr., dean of Boalt Hall, who is fielding anxious phone calls from faculty members and students.

"The analogy on everyone's mind here is the McCarthy era, when professors were harassed and sometimes prosecuted for their outside political endeavors," Mr. Edley says. "That explains the attractiveness of a bright-line rule that requires an actual criminal conviction before a professor can be disciplined for outside work." But Mr. Edley also says that a higher standard should apply to law professors and other instructors in professional schools. In those fields, Mr. Edley says, the university should investigate credible allegations of serious off-campus professional misconduct, even if a criminal conviction is nowhere in sight. "Law professors, after all, are charged with preparing the next generation of professionals to live their lives according to our ethical canons," he says. If the Justice Department's review includes serious allegations, Mr. Edley says, the university might be justified in formally reviewing Mr. Yoo's extracurricular activities. Such a move very likely would be triggered by the universitywide Academic Senate; the dean cannot initiate it. Mr. Edley emphasizes that he is speaking hypothetically, and he says that any punishment need not necessarily include revocation of tenure. The university's rules allow far milder sanctions, including written censure and a reduction in salary. The Merits of the Memos Mr. Yoo, who did not reply to repeated requests for an interview, has spent this semester as a visiting professor at Chapman University, in Southern California. Among his staunchest advocates is John C. Eastman, dean of Chapman's law school. Mr. Eastman not only argues against any academic punishment for Mr. Yoo but also defends Mr. Yoo's Justice Department memoranda on their merits. "After September 11 we were in uncharted territory," Mr. Eastman says. "Not since 1803, with the Barbary pirates, had we been in a war against a non-nation state. So I think the Office of Legal Counsel's job was to try to find out where the new lines were, ... and I think John actually got it right most of the time." Few other scholars agree. They note that the unrelenting theme of Mr. Yoo's memoranda was that the president and the executive branch had essentially unfettered powers to defend the country, and that Congress had no right to dictate the "method, timing, or place" of the president's wartime actions. The memoranda had broad consequences. They provided the legal rationale for the detention of José Padilla and other U.S. citizens deemed "unlawful combatants," and for a much-disputed domestic surveillance program, the details of which are still not known. The White House also cited Mr. Yoo's memoranda when it pressed the Defense Department to use coercive interrogation techniques, overriding objections from Pentagon lawyers that those techniques would violate the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Rejecting the Rationale Almost immediately after Mr. Yoo left the Justice Department, in 2003, his successor, Jack L. Goldsmith, took the rare step of revising and repudiating the memos. Mr. Goldsmith, who now teaches at Harvard University, is a conservative who broadly shares Mr. Yoo's views on presidential power and the Fourth Amendment. But as he recounted in his 2007 book,The Terror Presidency: Law and Judgment Inside the Bush Administration (W.W. Norton), he found that Mr. Yoo's memoranda "rested on cursory and one-sided legal arguments." The idea that Congress could not oversee the interrogation of detainees, he wrote, "has no foundation in prior OLC opinions, or in judicial decisions, or in any other source of law." Other scholars have offered even harsher judgments. Testifying before Congress in 2005, Harold Hongju Koh, dean of Yale Law School, called one of Mr. Yoo's memoranda "perhaps the most clearly erroneous legal opinion I have ever read." The question now being explored by the Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility is whether Mr. Yoo and his colleagues were not merely overzealous but were actively contriving rationales for illegal actions that they knew the administration was already undertaking. The department is reportedly reviewing e-mail messages and early drafts of the memoranda. "Evidence may emerge that supports a finding that Yoo essentially 'sold' his professionalism to the White House because he chose to give the executive branch what it wanted," says Stephen Gillers, a law professor at New York University. If such evidence does emerge, how should the University of California respond? Academic sanctions for outside legal work have been rare. One recent example on people's lips is the case of Mark M. Hager, who resigned from a tenured position at American University in 2003 not long after his law license was suspended for alleged misconduct in a product-liability lawsuit. (Neither the university nor Mr. Hager has acknowledged a link between his departure and his legal troubles.) But Mr. Hager's case is very different from the matters that are at issue with Mr. Yoo. Precisely because of the high stakes and the political sensitivities here, even many of Mr. Yoo's critics hope that his university will tread cautiously. "A lot of people, myself included, think that the memos represent serious failings of legal ethics, or possibly complicity in crime," says David J. Luban, a law professor at Georgetown University. "But academic tenure shouldn't depend on what people like me think. I think his tenure should be safe unless some impartial official body outside the university makes an independent finding that the memos are professional or criminal misconduct. " The law school should await an outside body, Mr. Luban and others say, because universities don't have the capacity to routinely review their law professors' outside legal practices. Moreover, universities would drive themselves crazy if they responded to public complaints about every controversial professor. Bill Clinton was disbarred for dishonesty; should he therefore have been denied a faculty position at the University of Arkansas? In the academic blogosphere, Mr. Yoo's status has been heatedly debated for more than a year by Brian R. Leiter, a professor of law at the University of Chicago, and J. Bradford DeLong, a professor of economics at Berkeley. Mr. Leiter, who is no fan of Mr. Yoo, insists that Mr. Yoo's academic position should be protected unless and until he is convicted of a crime. The university does not have the capacity to investigate Mr. Yoo's Justice Department work, Mr. Leiter argues. And even if it did, such an inquiry would open the floodgates for all kinds of politically tinged challenges to academic freedom. Mr. DeLong, though, believes that plenty of evidence already exists to justify a university review of Mr. Yoo's status. In an open letter last month to Berkeley's chancellor, Robert J. Birgeneau, Mr. DeLong urged the university to consider possible discipline. Academic freedom, he wrote, should not shield "those whose work is not the grueling labor of the scholar and the scientist but instead hackwork that is crafted to be convenient and pleasing to their political master of the day." Deep Ambivalence Mr. Yoo is not the only professor on the hot seat. In a case with close parallels, Tel Aviv University's law school was hit this month by protests against Pnina Sharvit-Baruch, a law instructor who has advised the Israeli government on the legitimacy of military strikes against civilian areas in Gaza. At Berkeley, meanwhile, many people view Mr. Yoo with deep ambivalence. Mr. Edley says that he and others feel affection for Mr. Yoo as a colleague. "He's never shirked his responsibility to put his views up for debate," Mr. Edley says. According to several accounts, some students have recently begun to shun Mr. Yoo's classes. "I would rather take constitutional law with someone who I am confident respects and upholds the rights guaranteed under the Constitution," says Lorraine Leete, a second-year student who is active in the National Lawyers Guild. But other students, even on the left, say that Mr. Yoo is a very strong teacher, and they support Mr. Edley's view that the university should wait for the Justice Department's report before taking any action. "Last year I took structural constitutional law with him," says Jonathan H. Singer, a second-year law student who is an editor of MyDD, a liberal blog. "In terms of being a professor, I found that he checked his views at the door. He was not doctrinaire. He was open to opinions. He stimulated discussion. I think there's great value in taking classes not just with professors you agree with, but with people who will challenge you." Patrick Bageant, another liberal second-year student, agrees that Mr. Yoo is excellent in the classroom. "A lot of people here feel, correctly, that the political process was probably corrupted when those memos were written," Mr. Bageant says. But like the law school's dean, Mr. Bageant says the university should not rush to judgment. It's "disturbingly ironic," Mr. Bageant says, that some of the same people who feel Mr. Yoo bent the law "are also willing to corrupt or bend the university's tenure rules to express their outrage about what took place." http://chronicle.com Section: The Faculty Volume 55, Issue 28, Page A12 | ||||